The term

“AI” has become overused, overextended, and marketed to oblivion like

“HD” or “3D.” A new product with “AI” in the headline of its press

release is thought to be more advanced. The time has come for us to

speak clearly about “artificial intelligence” (“AI”) and arrive at a

new, clean starting point from which to discuss things productively.

Let’s

begin with the words themselves, because if they are vague then we are

already obscuring things. Let’s accept “artificial” at face value: it

implies something synthetic, inorganic, not from nature, as in

“artificial sweetener” or “artificial turf”. So be it.

The painfully overcharged word here when paired with the word artificial is “intelligence”.

In thinking about artificial intelligence, I won’t refer to Alan Turing or his famous “test,”

for he himself pointed out (correctly) that this was meaningless. Nor

will I quote Marvin Minsky, who passed away recently concerned we were

repeating a so-called “AI Winter”: in that lofty expectations would lead

to disappointment and an under-investment in the science for years. His worries are well founded, and that’s a different discussion. Another separate discussion is AI’s existential threat to humanity, which Bostrom, Musk, Kurzweil and others have pondered.

Instead let’s look at what nearly all of the software carrying the label “AI” is doing and how it relates to working with information.

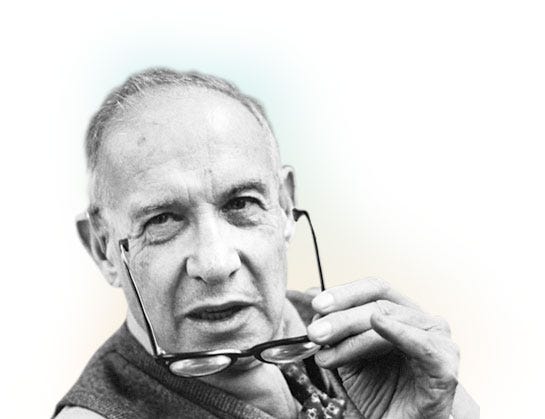

I’ve been among the many who have long admired the thinking and writing of Peter Drucker. His clarity of thought is reminiscent of prior generation Austrian writers, including Zweig and Rilke.

So what would Drucker say about artificial intelligence?

Drucker would say that we are mostly talking about machines performing knowledge work. He would view the “intelligence” label as chimerical.

The

term “knowledge worker” was coined by Drucker, who said in 1957 that

“the most valuable asset of a 21st-century institution, whether business

or non-business, will be its knowledge workers and their productivity.”

The

utility of this term was to distinguish laborers (farmers, machinists,

construction workers, etc.) in the workforce from a new emerging type of

worker (accountants, architects, lawyers, etc.) who worked primarily with information.

Knowledge Work and Software

Here’s

where it gets interesting. This new frontier of work “by thinking”

certainly did not exclude machines — more accurately: computers — more

specifically: software. That’s because the new knowledge-working genre

that Drucker perceived in the 1950s was just beginning to interact with

computers. Now of course, software has increasingly augmented and

replaced human work as it relates to information, and today it is a

pervasive phenomenon.

In

fact, a software spreadsheet (one of the most useful and common pieces

of software ever created) is capable of knowledge work. It’s doing a

fair amount of the work that was done previously by calculators, and

prior to that — a mano by

number crunching humans. The spreadsheet is performing tasks that were

once performed by a human knowledge worker. That is what it does.

We

don’t refer to the work of an accounting package, a travel booking

server, a payroll processor, CAD (computer aided design), and countless

other software systems as “AI”.

Software

has for a long time performed knowledge work and this work has evolved

in complexity for decades. It has done so in narrowly defined tasks,

always with a specific goal in mind. This is still true today.

The evolution of software as a knowledge worker

What

about the “AI” that recognizes patterns in stock market data,

translates writing from one language to another, transcribes audio or

recognizes image patterns? This is also software applied to knowledge work.

We’re

referring to a set of instructions applied to a computer system (CPU,

memory, etc.) to move data around, calculate and output values. Today we

have have a lot more “system” today than ever before, and we have a lot

more data as well.

The fact that software is now doing its thing increasingly everywhere is a big thing.

It is able to perform “knowledge work” in your car, in your hands, and

in the world. It is able to do this kind of work while being connected

to informational resources. Knowledge work, as Drucker pointed out, is

intrinsically about information.

The primary difference between today’s knowledge worker and yesterday’s is the amount of processing and information at hand.

What is deceivingly branded “AI” today is based on old algorithms (eg.

neural networks, invented decades ago) applied to larger computing and

datasets.

Intelligence?

Herein

lies the significance of the term “intelligence”. A laborer is

undoubtedly intelligent, a farmer deals with extraordinary amounts of

information about crops, soil, weather, etc. But farmers are not

knowledge workers, because their craft is not predominantly working with

information, that’s secondary to the actual task at hand. The

accountant, also intelligent, is on the other hand primarily working

with information.

This is not about “intelligence”, but rather what they are working on, the nature of the work.

Just as knowledge work can be the job of a person, artificial knowledge work can be the job of a software application. This

is what the vast majority of software with the “AI” branding is

actually doing. But just because it’s called Artificial Intelligence doesn’t mean the software has any intelligence. But that too may be changing.

A

field known as “Artificial General Intelligence”, or “AGI” is examining

the possibility of software that can “think” in the pure sense of the

word. What is referred to as “AGI” should simply and properly be called

“AI” because once machines can acquire knowledge, learn adaptively and

make rational choices, they become not just knowledge workers, but truly

intelligent.

In conclusion, software continues to evolve in its capacity to perform knowledge work: narrowly defined information-driven tasks with specific objectives. The label “intelligence” has to do with something much more fundamental and elusive.

The

human accountant has the ability to learn to be an architect (a

different type of knowledge worker) but today’s artificial knowledge

worker cannot adapt this way. Software code can “learn” but thus far

only within a specific type of task. DeepMind’s “AlphaGo” defeated a Go

professional player but it cannot play checkers, tic-tac-toe, or any other game.

The “smartest” software applied in consumer and business settings today

lacks the capacity to adapt itself outside of its intended purpose. It

is utilitarian.

The scientific pursuit of artificial intelligence aims to change this. Will we see real advancements on this front? Are you ready?

No comments:

Post a Comment